Internet Art the Online Clash of Culture and Commerce

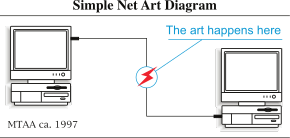

"Simple Net Art Diagram", a 1997 work past Michael Sarff and Tim Whidden

Internet fine art (also known every bit internet fine art) is a form of new media art distributed via the Internet. This form of art circumvents the traditional dominance of the concrete gallery and museum system. In many cases, the viewer is drawn into some kind of interaction with the piece of work of art. Artists working in this manner are sometimes referred to every bit cyberspace artists.

Net artists may use specific social or cultural internet traditions to produce their art exterior of the technical structure of the net. Internet fine art is often — just not e'er — interactive, participatory, and multimedia-based. Cyberspace art can be used to spread a message, either political or social, using man interactions.

The term Cyberspace fine art typically does not refer to art that has been but digitized and uploaded to exist viewable over the Net, such as in an online gallery.[1] Rather, this genre relies intrinsically on the Net to exist as a whole, taking advantage of such aspects as an interactive interface and connectivity to multiple social and economic cultures and micro-cultures, not just web-based works.

New media theorist and curator Jon Ippolito defined "Ten Myths of Internet Art" in 2002.[1] He cites the above stipulations, too equally defining it as distinct from commercial web design, and touching on issues of permanence, archivability, and collecting in a fluid medium.

History and context [edit]

Net art is rooted in disparate artistic traditions and movements, ranging from Dada to Situationism, conceptual art, Fluxus, video fine art, kinetic art, functioning art, telematic art and happenings.[2]

In 1974, Canadian artist Vera Frenkel worked with the Bell Canada Teleconferencing Studios to produce the work String Games: Improvisations for Inter-Metropolis Video, the first artwork in Canada to use telecommunications technologies.[3]

An early telematic artwork was Roy Ascott'south piece of work, La Plissure du Texte,[4] performed in collaboration created for an exhibition at the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1983.

In 1985, Eduardo Kac created the animated videotex verse form Reabracadabra for the Minitel system.[five]

Media art institutions such as Ars Electronica Festival in Linz, or the Paris-based IRCAM (a enquiry center for electronic music), would also back up or nowadays early networked art. In 1997 MIT's Listing Visual Arts Center hosted "PORT: Navigating Digital Culture," which included cyberspace art in a gallery infinite and "time-based Internet projects."[vi] Artists in the show included Cary Peppermint, Prema Murthy, Ricardo Dominguez, and Adrianne Wortzel. In 2000 the Whitney Museum of American Art included net art in their Biennial exhibit.[7] Information technology was the first time that internet art had been included as a special category in the Biennial, and it marked one of the earliest examples of the inclusion of internet art in a museum setting. Internet artists included Marking Amerika, Fakeshop, Ken Goldberg, etoy and ®™ark.

With the rise of search engines as a gateway to accessing the web in the late 1990s, many net artists turned their attention to related themes. The 2001 'Data Dynamics' showroom at the Whitney Museum featured 'Netomat' (Maciej Wisniewski) and 'Apartment' (Marek Walczak and Martin Wattenberg), which used search queries as raw cloth. Mary Flanagan's ' The Perpetual Bed' received attention for its use of 3D nonlinear narrative infinite, or what she chosen "navigable narratives."[8] [9] Her 2001 slice titled 'Collection' shown in the Whitney Biennial displayed items amassed from difficult drives effectually the earth in a computational collective unconscious.'[10] Golan Levin'south 'The Surreptitious Lives of Numbers' (2000) visualized the "popularity" of the numbers 1 to 1,000,000 every bit measured by Alta Vista search results. Such works pointed to alternative interfaces and questioned the dominant office of search engines in controlling access to the internet.

Yet, the Internet is not reducible to the web, nor to search engines. Besides these unicast (indicate to signal) applications,suggesting the existence of reference points, there is also a multicast (multipoint and uncentered) internet that has been explored by very few artistic experiences, such as the Poietic Generator. Internet art has, co-ordinate to Juliff and Cox, suffered under the privileging of the user interface inherent within calculator art. They argue that Cyberspace is non synonymous with a specific user and specific interface, but rather a dynamic structure that encompasses coding and the artist's intention.[11]

The emergence of social networking platforms in the mid-2000s facilitated a transformative shift in the distribution of internet art. Early online communities were organized around specific "topical hierarchies",[12] whereas social networking platforms consist of egocentric networks, with the "private at the center of their own community".[12] Creative communities on the Internet underwent a similar transition in the mid-2000s, shifting from Surf Clubs, "xv to xxx person groups whose members contributed to an ongoing visual-conceptual conversation through the use of digital media"[13] and whose membership was restricted to a select grouping of individuals, to image-based social networking platforms, similar Flickr, which permit access to any individual with an e-mail accost. Internet artists make all-encompassing employ of the networked capabilities of social networking platforms, and are rhizomatic in their organization, in that "product of significant is externally contingent on a network of other artists' content".[13]

Post-Cyberspace [edit]

Post-Cyberspace movements are responsible for Net-centric microgenres and subcultures such as vaporwave[14]

Post-Internet is a loose descriptor[14] for works that are derived from the Internet or its effects on aesthetics, civilisation and society.[fifteen] It is a controversial and highly criticized term in the art community.[14] It emerged from mid-2000s discussions almost Cyberspace art by Marisa Olson, Gene McHugh, and Artie Vierkant (the latter notable for his Prototype Objects, a series of deep blue monochrome prints).[sixteen] Between the 2000s and 2010s, post-Internet artists were largely the domain of millennials operating on web platforms such as Tumblr and MySpace. The movement is too responsible for spearheading slews of microgenres and subcultures such as seapunk and vaporwave.[14]

This term "post internet" was coined by Internet artist Marisa Olson in 2008.[17] Co-ordinate to a 2015 article in The New Yorker, the term describes "the practices of artists who ... dissimilar those of previous generations, [utilise] the Web [as] just another medium, similar painting or sculpture. Their artworks move fluidly between spaces, appearing sometimes on a screen, other times in a gallery."[eighteen] In the early 2010s, "post-Internet" was popularly associated with the musician Grimes, who used the term to depict her work at a time when post-Internet concepts were not typically discussed in mainstream music arenas.[19]

Tools [edit]

Fine art historian Rachel Greene identified six forms of cyberspace art that existed from 1993 to 1996: electronic mail, audio, video, graphics, blitheness and websites.[20] These mailing lists allowed for organization which was carried over to face-to-face meetings that facilitated more than nuanced conversations, less burdened from miscommunication.

Since the mid-2000s, many artists take used Google's search engine and other services for inspiration and materials. New Google services breed new artistic possibilities.[21] Commencement in 2008, Jon Rafman collected images from Google Street View for his project chosen The 9 Eyes of Google Street View.[22] [21] Another ongoing net art projection is I'm Google by Dina Kelberman which organizes pictures and videos from Google and YouTube around a theme in a filigree form that expands as you ringlet.[21]

See also [edit]

- Art sales

- Artmedia

- ASCII art

- Cyberculture

- Cyberformance

- Digital art

- Electronic mail art

- Fax art

- Fractal art

- Homestuck

- Hypertext fiction

- Net.art

- Net-poetry

- Online exhibition

- SITO

- Surfing lodge

- Telematic fine art

- Tradigital art

- Virtual art

References [edit]

- ^ a b Ippolito, Jon (2002-10-01). "Ten Myths of Internet Fine art". Leonardo. 35 (5): 485–498. doi:10.1162/002409402320774312. ISSN 0024-094X. S2CID 57564573.

- ^ Chandler, Annmarie; Neumark, Norie (2005). At a Distance: Precursors to Art and Activism on the Internet. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN0-262-03328-3.

- ^ Langill, Caroline (2009). "Electronic media in 1974". Shifting Polarities. Montreal: The Daniel Langlois Foundation for Fine art, Scientific discipline, and Technology. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

- ^ White, Norman T. "Plissure du Texte". The NorMill . Retrieved September 21, 2010. (Unedited transcript including organizational word.)

- ^ "NET Fine art Album: Reabracadabra". NET ART ANTHOLOGY: Reabracadabra. 2016-x-27. Retrieved 2020-12-26 .

- ^ "Port Home".

- ^ The Whitney Biennial 2000. See too "At present Anyone Can Be in the Whitney Biennial" in The New York Times (March 23, 2000), and "The Whitney Speaks: It Is Art" in Wired Magazine (March 23, 2000).

- ^ Klink, Patrick (1999). "Daring Digital Artist". UB Today. Buffalo: The Academy at Buffalo. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Flanagan, Mary (2000). "navigating the narrative in space: gender and spatiality in virtual worlds". Art Journal. New York: The College Art Association. Retrieved Dec 21, 2011.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (2002). "Never Mind the Art Police, These Six Matter". The New York Times. New York. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ Toby Juliff, Travis Cox (2015). "The post-display status of gimmicky figurer fine art" (PDF). EMaj. 8.

- ^ a b Boyd, D. M.; N. B. Ellison (2007). "Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 13 (one): 210–230. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x. S2CID 52810295. Retrieved xx November 2012.

- ^ a b Schneider, B. "From Clubs to Affinity: The Decentralization of Fine art on the Internet". 491. Archived from the original on seven July 2012. Retrieved 20 Nov 2012.

- ^ a b c d Amarca, Nico (March 1, 2016). "From Bucket Hats to Pokémon: Breaking Down Yung Lean's Mode". High Snobiety . Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ^ Wallace, Ian (March 18, 2014). "What Is Post-Internet Art? Agreement the Revolutionary New Fine art Motility". Artspace.

- ^ Connor, Michael (November 1, 2013). "What'due south Postinternet Got to do with Net Fine art?". Rhizome.

- ^ "Interview with Marisa Olson". 28 March 2008.

- ^ Kenneth, Goldsmith (2015-03-x). "Mail service-Internet Verse Comes of Historic period". The New Yorker . Retrieved 2016-09-14 .

- ^ Snapes, Laura (February 19, 2020). "Pop star, producer or pariah? The conflicted brilliance of Grimes". The Guardian.

- ^ Moss, Cecelia Laurel (2015). Expanded Net Fine art and the Informational Milieu. Ann Arbor. p. 1. ISBN978-1-339-32982-half dozen. </5-Arts Cyberspace> In the 1990s, e-mail based mailing lists provided net artists with a community for online discourse that broke boundaries between critical and generative dialogues. The electronic mail format allowed instant expression, however limited to text and simple graphic based communication, with an international scope.<5-arts net>Greene, Rachel. (2004). Internet art. New York, N.Y.: Thames & Hudson. pp. 73–74. ISBN0-500-20376-8. OCLC 56809770.

- ^ a b c Christou, Elisavet (2018-07-01). "Internet Art, Google and Artistic Practice". Electronic Workshops in Computing. doi:x.14236/ewic/EVA2018.23.

- ^ "Internet ART ANTHOLOGY: Nine Eyes of Google Street View". Net ART Anthology: Nine Eyes of Google Street View. 2016-10-27. Retrieved 2020-11-xvi .

Bibliography [edit]

- Kate Armstrong, Jeremy Bailey & Faisal Anwar on Net Art in Canadian Fine art Magazine [1] [ permanent dead link ]

- Weibel, Peter and Gerbel, Karl (1995). Welcome in the Internet World , @rs electronica 95 Linz. Wien New York: Springer Verlag. ISBN iii-211-82709-9

- Fred Wood 1998,¨Cascade united nations art actuel, l'art à l'heure d'Internet" l'Harmattan, Paris

- Baranski Sandrine, La musique en réseau, une musique de la complexité ? Éditions universitaires européennes, mai 2010

- Barreto, Ricardo and Perissinotto, Paula. "the_culture_of_immanence". Archived from the original on 29 September 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Baumgärtel, Tilman (2001). net.art ii.0 – Neue Materialien zur Netzkunst / New Materials towards Internet art. Nürnberg: Verlag für moderne Kunst. ISBN 3-933096-66-9.

- Wilson, Stephen (2001). Data Arts: Intersections of Fine art, Science and Engineering science. Cambridge, Massachusetts : MIT Printing. ISBN 0-262-23209-X.

- Caterina Davinio 2002. Tecno-Poesia e realtà virtuali / Techno-Poesy and Virtual Realities, Sometti, Mantua (Information technology) Collection: Archivio della poesia del 900. Mantua Municipality. With English language translation. ISBN 88-88091-85-viii

- Stallabrass, Julian (2003). "Internet Fine art: the online clash of culture and commerce". Tate Publishing. ISBN 1-85437-345-5, ISBN 978-1-85437-345-8.

- Christine Buci-Glucksmann, "L'art à 50'époque virtuel", in Frontières esthétiques de l'fine art, Arts 8, Paris: L'Harmattan, 2004

- Greene, Rachel (2004). "Net Fine art". Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20376-8, ISBN 978-0-500-20376-vii.

- Corby, Tom (2006). "Network Fine art: Practices and Positions". Routledge, ISBN 0-415-36479-five.

- WB05 e-symposium published as ISEA Newsletter #102 - ISSN 1488-3635 #102 [2]

- Juliff, Toby & Cox, Travis. 'The Post-display condition of contemporary figurer art.' eMaj #8 (Apr 2015) https://emajartjournal.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/cox-and-juliff_the-post-display-condition-of-gimmicky-computer-art.pdf

- Ascott, R.2003. Telematic Embrace: visionary theories of art, technology and consciousness. (Edward A. Shanken, ed.) Berkeley: Academy of California Press.

- Roy Ascott 2002. Technoetic Arts (Editor and Korean translation: YI, Won-Kon), (Media & Art Series no. 6, Establish of Media Fine art, Yonsei University). Yonsei: Yonsei University Press

- Ascott, R. 1998. Fine art & Telematics: toward the Structure of New Aesthetics. (Japanese trans. E. Fujihara). A. Takada & Y. Yamashita eds. Tokyo: NTT Publishing Co.,Ltd.

- Fred Wood 2008. Fine art et Net, Paris Editions Cercle D'Art / Imaginaire Mode d'Emploi

- Thomas Dreher: IASLonline Lessons/Lektionen in NetArt.

- Thomas Dreher: History of Computer Art, chap.Six: Cyberspace Art: Networks, Participation, Hypertext

- Monoskop (2010). Overview of 'surf clubs' phenomenon. [3]

- Fine art in the Era of the Internet, PBS Written report

- (in Spanish) Martín Prada, Juan, Prácticas artísticas e Internet en la época de las redes sociales, Editorial AKAL, Madrid, 2012, ISBN 978-84-460-3517-6

- Bosma, Josephine (2011) "Nettitudes - Let'south Talk Net Fine art" [four] NAI Publishers, ISBN 978-90-5662-800-0

- Schneider, B. (2011, January half dozen). From Clubs to Affinity: The Decentralization of Art on the Net « 491. 491. Retrieved March 3, 2011, from https://spider web.archive.org/web/20120707101824/http://fourninetyone.com/2011/01/06/fromclubstoaffinity/

- Boyd, D. Thousand.; Ellison, North. B. (2007). "Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 13 (1): 210–230. doi:x.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.10. S2CID 52810295.

- Moss, Ceci. (2008). Thoughts on "New Media Artists v. Artists with Computers". Rhizome Periodical. http://rhizome.org/editorial/2008/december/3/thoughts-on-quotnew-media-artists-vs-artists-with-/

- Greene, Rachel. (2000) A History of Cyberspace Art. Artforum, vol. 38.

- Bookchin, Natalie & Alexei Shulgin (1994-5). Introduction to net.art. Rhizome. http://rhizome.org/artbase/artwork/48530/.

- Atkins, Robert. (1995). The Art Earth (and I) Become Online. Art in America 83/2.

- Houghton, B. (2002). The Net & art: A guidebook for artists. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-089374-9.

- Bosma, J. (2011). Nettitudes: Let'due south talk internet art. Rotterdam: Nai Publishers. ISBN 978-90-5662-800-0.

- Daniels, D., & Reisinger, G. (2009). Net pioneers ane.0: Contextualizing early internet-based art. Berlin: Sternberg Press. ISBN 978-1-933128-71-9.

External links [edit]

- netartnet.internet an online-gallery listing and directory of internet art

- > ¿netart or notart? < netart latino database

- "Post-Internet Materialism". metropolism.com . Retrieved 2015-03-fifteen . An interview with Martijn Hendriks & Katja Novitskova

- "The New Aesthetic and its Politics"

- "Finally, a Semi-Definitive Definition of Post-Net Art". Fine art F Urban center. 14 October 2014.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_Art

0 Response to "Internet Art the Online Clash of Culture and Commerce"

Post a Comment